A comparative analysis of U.S. government agencies’ AI inventories

It has been almost a year since U.S. government agencies published their first annual Artificial Intelligence (AI) inventories. Soon, each agency will be expected to prepare and introduce their second annual inventory. The inventories were published in response to Executive Order 13960, a December 2020 order intended to increase transparency around how AI is used by the federal government and to promote trustworthy AI by federal agencies.

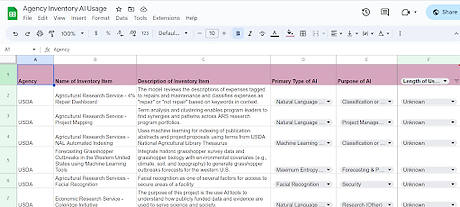

To better understand how and why federal agencies are using Artificial Intelligence, I reviewed each of the inventories and built a database that categorizes the use cases based on: type of AI used, purpose of AI used, length of project, and impact of the AI on the public. Then, I analyzed the database to draw some conclusions about how AI is being used. Before diving into the results from the analysis, I will point out a few things about the inventories.

First, the inventories are incomplete. Several agencies offer extensive lists, while others include only one or two use cases in their inventories. The limited lists may result from administrative delays, but they may also be due to low usage of AI at those departments or difficulty categorizing use cases that may or may not be considered AI. The Department of Education, for example, only has one use case in its inventory as of April 2023: the Aidan chat bot belonging to the student aid process. It is worth reflecting on whether low usage is worth criticizing, since some parts of the government do not take advantage of technology that could make their work more efficient and less resource-intensive, or celebrating, because agencies are treading carefully when it comes to a new disruptive technology.

Second, the Executive Order requires only that agencies include non-classified and non-sensitive use cases of AI. As a result, the database is not wholly representative of agency AI use cases, since some use cases might not be disclosed to the public. The Department of Transportation, for instance, had three rows in their inventory labeled as “redacted,” which might have been due to information security concerns. Four agencies (HUD, USAID, NIST, and NSF) claimed on their websites not to use AI in their operations or to have identified no “relevant” AI use cases. It is difficult to believe that the NIST does not use AI in its projects, but if it truly does not, why is that? It is possible that none of the NIST use cases were considered non-classified and non-sensitive. It is also possible that the federal government needs to encourage better information- and resource-sharing between agencies so that AI-driven tools are appropriately exchanged and distributed.

The stark disparities in the lengths of inventories (Department of Interior, for instance, has 65 use cases) raise questions about how and why agencies utilize artificial intelligence. My database sheds some light on those questions.

Summary of Results

In total, the database includes 337 use cases. Agencies deployed a wide range of AI types, from decision tree analysis (such as random forest) to optical character recognition (and text extraction). Several of the inventories did not specify the type of AI used, so the type of AI was inferred based on the project description or labeled as unclear.

Analysis shows that agencies deployed very little facial recognition technology, except for security purposes on government property. Natural language processing (NLP) was the most commonly-deployed type of AI and was often used to ensure that limited resources were used thoughtfully and effectively. For instance, the General Services Administration uses NLP to determine which comments on the USA.gov comments section are worth the time of analysts, who need to individually read and sort them. 71 out of the 337 use cases were still in the planning or development stage and 19 projects involved only short-term studies or experiments, although it’s worth pointing out that many of the inventories did not include any timeline information on their projects so it was difficult to accurately gauge length of the project.

AI use cases were sorted into one of nine predetermined categories that characterized the primary purpose of the project. 23% of the use cases were intended to help the federal government predict future outcomes. USDA uses maximum entropy modeling to forecast grasshopper outbreaks in the Western United States since invasive grasshoppers can wreak havoc on farm harvests. AI was used for monitoring or detection in 17.8% of use cases, including a classifier from the Department of Justice that scans documents and looks for attorney/client privileged information and a model from the Department of Homeland Security that automatically detects potential personally-identifiable information in forms submitted to the agency.

One of the columns that distinguishes the database from the federal agency inventories is a column titled “Does it directly impact the public?” The intent of this column is to better understand if and why the American public should care about how AI is being used by the federal government. This column (which includes three options: “No Impact,” “Indirect Impact,” and “Direct Impact”) was formulated based on subjective third-party understanding of each project. Anytime the data of individuals was used to inform the model, even if the data was anonymized, I considered the impact of the project on the public to be at least indirect. However, there were still instances where impact was unclear, such as a Department of Energy project called “Protocol Analytics to enable Forensics of Industrial Control Systems,” which was described by DoE as “bridging gaps between the various industrial control systems communication protocols and standard Ethernet to enable existing cybersecurity tools to defend ICS networks and empower cybersecurity analysts to detect compromise before threat actors can disrupt infrastructure, damage property, and inflict harm.” Given the implications for civilians if essential infrastructure was hampered, I considered that project as having impact on the public although the public does not engage or interact with it.

21% of the use cases had a direct impact on the public. Most of those use cases stemmed from the Department of Veterans Affairs, which uses AI to monitor the health of veterans and provide recommendations to medical teams. In general, though, the database shows that agencies tend to use AI where there’s no risk for direct negative impact to the public. Depending on outlook, that finding could be considered a win or a loss. On one hand, it appears that AI is not used as invasively

or abusively by the federal government as some might lead us to believe. On the other hand, if we believe that AI can generate benefits for the federal government in three ways (smarter policymaking, reimagined service delivery, and more efficient operations), then it seems that the federal government is falling short of using AI to its full potential to provide Americans with new and improved services.

Discussion

The intent of this research is not to issue absolute judgements on how and why the U.S. government uses AI. However, this database does provide insight into how federal agency AI inventories can be made more useful in the future, for researchers and within the government.

- Promote Playbook for Responsible AI: Two agencies (DOD and HHS) have created a playbook to help their departments follow principles of responsible AI. Other agencies can and should adopt similar guidelines to ensure AI programs are built with the principles of fairness, accountability and transparency.

- Understand Inventory Impact on the General Public: The inventories don’t capture autonomy very neatly; there is no information about the extent there is a human in the loop when it comes to decision-making informed by artificial intelligence. Anecdotally, the database results suggest that – when there is direct impact to the public – humans make the final decision (not machines). Many inventories also outlined plans for evaluating and monitoring AI models to see how they compared to manual analysis by humans, suggesting that agency usage can be ethical.

- Standardize Inventory Format: Agencies need to standardize how and what they report in their inventories since the language, format, and depth of information varied tremendously across websites. For example, very few agencies reported the length of time the AI use case had been in operation, except for a few standout agencies like the Department of Interior. The Executive Order is not serving its purpose of increasing transparency into AI-driven operations if the public cannot understand how taxpayer money is being used to facilitate AI implementation.

- Improve Access to Essential Information: There is no dollar amount attached to any of the inventories. It is difficult to ascertain the value added of each use case and to see how much AI use cases have improved agency operations until we have clear information on how much money, time, or resources were saved. On a similar note, the inventories do not include AI use cases that were “retired” when they were found to not be in compliance with Executive Order 13960. This hampers insight into how much the EO improved the responsible use of AI in the federal government.

- Introduce Collaborative Inventory Audit: The only large overlap in inventory projects was between the Department of Interior and the Department of Commerce, which both used AI to track animal species and monitor their movements. Agencies should meet annually to compare and audit their inventories to see how they can collaborate to use resources wisely and avoid project duplication.

About Responsible AI Institute (RAI Institute)

Founded in 2016, Responsible AI Institute (RAI Institute) is a global and member-driven non-profit dedicated to enabling successful responsible AI efforts in organizations. We accelerate and simplify responsible AI adoption by providing our members with AI conformity assessments, benchmarks and certifications that are closely aligned with global standards and emerging regulations.

Members include leading companies such as Amazon Web Services, Boston Consulting Group, ATB Financial and many others dedicated to bringing responsible AI to all industry sectors.

Media Contact

Nicole McCaffrey

Head of Marketing, RAI Institute

nicole@responsible.ai

+1 (440) 785-3588

Follow RAI Institute on Social Media